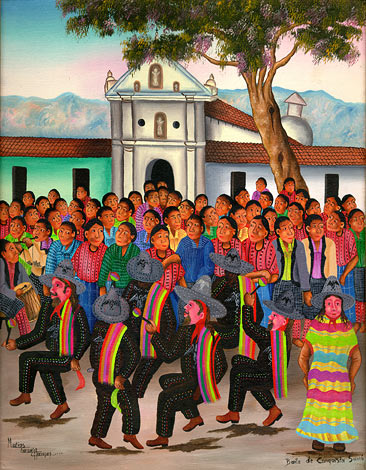

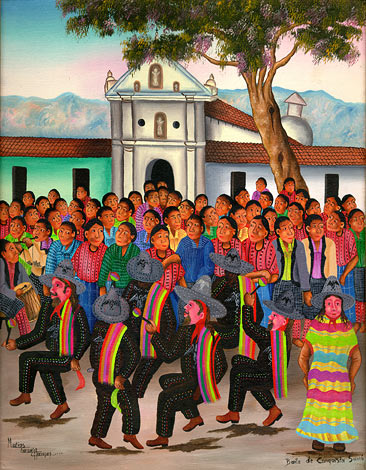

Baile de Conquista

(Dance of the Conquest)

1990

20" x 16", oil on canvas

Matias Gonzalez Chavajay

I have always enjoyed this painting a great deal, and on the surface it is easy to see what is it is about—as part of a fiesta the people of Sololá are watching costumed dancers in one of the traditional Guatemalan masked dances. If one delves deeper into the theme of this particular painting, one becomes confused. The artist seems confused about what exactly he is painting, and what it seems he is painting, the Baile Mexicano, does not seem historically accurate. It is more confusing to me because this painting was one of a pair of paintings that Matias finished at about the same time, this one entitled Baile de Conquista and the other one entitled Baile Mexicano. Unfortunately I did not acquire both of them.

Although this painting is titled Baile de Conquista, it is almost certainly a depiction of the Baile Mexicano. In both of these masked dances, the dancers wear similar carved and painted wooden masks. In the Baile de Conquista, the conquistadores have elaborate and fanciful costumes while in the Baile Mexicano they wear costumes representing charros. Here we see men dressed in identical black costumes, tight black pants and jacket and a grey sombrero-like hat. To the side there is also a odd-looking woman who is also wearing a sombrero. This woman is a male dancer, as are all dancers, wearing a mask and dressed as a woman. She has been identified as La Melinche, the Indian slave who was given to Hernan Cortez, bore him a son, and translated for him assisting in the conquest but possibly preventing much bloodshed as Cortez was able to make negotiations.

Anyone who knows the work of Matias knows that he makes mistakes such as this, whether consciously or unconsciously, and this is part of the charm of the naivete of his paintings. [One charming painting I had was of men cutting down bananas from a tree, but the leaves were not smooth banana leaves but the serrated leaves of a palm.]

In this painting men dressed in black with bright pink masks dance for a crowd in front of a

the church. Only one person is looking at the dancers and that one person is cross-eyed; the others are all looking to the left or the right of the dancers.

Thus, when Cortez arrived at Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, Moctezuma greeted him warmly and even kissed his hand. By this point, Cortez had a translator, a woman named Malinche (sometimes called Dona Marina). She had joined the war party and Malinche made possible communication between Cortez and Moctezuma.

There is none. There is a monument to Columbus, who never set foot in Mexico, and one to Cuauhtéémoc, the last Aztec leader, whose capture on August 13, 1521, marked the fall of one great empire and the rise of another. But Cortéés, who more than any other individual shaped the future of the country and arguably the world, is almost uniformly vilified in Mexico today. When I confessed to one Mexican amiga that I had a certain admiration for the man, she turned to me with derision: "You admire a thief and a torturer?"

La Malinche, his consort, translator and advisor, without whom the diplomatic maneuvering which was as much a part of the conquest as the fighting would have been impossible, is often regarded as a whore and traitor. Her name has come to be used to describe a person who turns his back on his own culture: malinchista.

That Cortéés was able to wheel and deal with the natives on a complex level was due to two great strokes of luck. The first, while he was still at Cozumel, was the addition to his band of Jeróónimo de Aguilar, a priest who had been shipwrecked on the coast eight years before and kept as a slave by Yucatan Mayas. He spoke Spanish and Mayan.

Then, after their first military victory in what is now the state of Tabasco, they received among other forms of tribute 20 Indian women; one of them was Malinche, christened Doñña Marina. Malinche was the daughter of the lord of a Nááhuatl-speaking town. After her father died and her mother remarried, she became an inconvenient stepchild and was secretly sold as a slave to a Mayan lord, while her mother and stepfather gave out that she had died. Now she had been given to these strangers. No one could have guessed how important that would be.

Now Cortéés could speak to the Aztecs, not with grunts and signs but with precise and often devious detail. Cortéés would speak to Aguilar in Spanish, Aguilar would speak to Malinche in Mayan, and she would translate into Nááhuatl, the lingua franca of the central Mexican highlands.

We spent an afternoon at the ruins of Quiahuiztláán with a young musician from Jalapa. Sitting on the spot where I imagine Cortéés sat, staring out at the sea and plotting the conquest of Mexico, I asked him what he thought of La Malinche. "Was she a traitor or a heroine? Didn't she have reason to oppose the tyranny and oppression gripping Mexico, and to hope for relief from the powerful strangers?"

"It is a story of love," he told me. "Love is more important than politics."

All historians agree that she was the daughter of a noble Aztec family. Upon the death of her father, a chief, her mother remarried and gave birth to a son. Deciding that he rather than Marina, should rule, she turned her young daughter over to some passing traders and thereafter pro- claimed her dead. Eventually, the girl wound up as a slave of the Cacique (the military chief) of Tabasco. By the time Cortes arrived, she had learned the Mayan dialects used in the Yucatan while still understanding Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and most Non-Mayan Indians.

"La Malinche" did not choose to join Cortes. She was offered to him as a slave by the Cacique of Tabasco, along with 19 other young women. She had no voice in the matter.

Up till then, Cortes had relied on a Spanish priest, Jeronimo de Aguilar, as his interpreter. Shipwrecked off Cozumel, Aguilar spoke the Mayan language as well as Spanish. But when the expedition left the Mayan-speaking area, Cortes discovered that he could not communicate with the Indians. That night he was advised that one of the women given to him in Tabasco spoke "Mexican."

Doñña Marina now enters Mexican history. It was she who served as the interpreter at the first meetings between Cortes and the representatives of Moctezuma. At that time Marina spoke no Spanish. She translated what the Aztecs said into the Mayan dialect understood by de Aguilar and he relayed it to Cortes in Spanish. The process was then reversed, Spanish to Mayan and Mayan to Nahuatl.

Bernal Diaz, author of "The Conquest of New Spain" authenticated her pedigree. An eyewitness to the events, he did not describe her physically, but related that after the Conquest he attended a reunion of Doñña Marina, her mother and the half- brother who had usurped her rightful place. Diaz marveled at her kindness in forgiving them for the injustice she had suffered. The author referred to her only as Marina or Doñña Marina. So whence came the name "La Malinche?" Diaz said that because Marina was always with Cortes, he was called "Malinche"--which the author translated to mean "Marina's Captain." Prescott, in the "Conquest of Mexico," (perhaps the best known book on the subject) confirms that Cortes was always addressed as "Malinche" which he translated as Captain and defined "La Malinche" as "the captain's woman."

Both definitions confirm that the Indians saw Cortes and his spokesperson as a single unit. They recognized that what they heard were the words of "Malinche," not "La Malinche. " So much for the charge that she was a traitor, instigating the destruction of the Aztec Empire.

As for the charge of "harlotry," it is equally flawed. She was totally loyal to Cortes, a one-man woman, who loved her master. Cortes reciprocated her feelings. Time after time he was offered other women but always refused them. Bernal Diaz frequently commented on the nobility of her character and her concern for her fellow "Mexicans."

It is very possible that without her, Cortes would have failed. He himself, in a letter preserved in the Spanish archives, said that "After God we owe this conquest of New Spain to Doñña Marina. "

Doñña Marina's progress from interpreter to secretary to mistress, as well as her quick mastery of Spanish, are remarkable--and all this amidst the turmoil of constant warfare, times when a woman less courageous and committed might well have fled.

The ability of Marina to help Cortes to communicate with the Indians shaped the entire campaign. From the very first meeting between Cortes and the emissaries of Moctezuma, an effort was made to establish friendly relations with the Aztec Emperor.

Later, during Cortes's encounter with the Caciques of Cempola, that same talent opened the door to the Conquest. Here, Cortes met the "Fat Cacique" and by arresting five tax collectors sent by the Aztecs, made his first Indian allies: Cempoalans were the first of the Indian warriors to join him.

Yet even then, he tried to persuade Moctezuma to invite him to Tenochtitlan, freeing the captives to carry a message to the Emperor that he had come in peace.

Without Marina, attempts to negotiate with the Aztecs would have been impossible.

These efforts did much to keep Moctezuma undecided about how to deal with the invaders. This hesitancy played a large part in the outcome of the Conquest.

Perhaps the most important negotiations Marina made possible were those with the Tlascalans. After an initial armed clash, an alliance was forged that brought thousands of warriors to fight alongside the Spaniards.

As Cortes moved toward the Aztec capital, a pattern evolved.

First conflict, then meetings in which Doñña Marina played a key role in avoiding more bloodshed. Hence, the picture of Marina that emerges is that of an intelligent, religious, loyal woman.

Her contribution to the success of the Conquest is immense, but she cannot be held responsible for it happening. To a very large degree, the Conquest came because of the brutality of the Aztecs: a rebellion by their oppressed neighbors, who would have rallied to anyone who promised them relief from the Aztecs' constant demands for tribute and sacrificial victims.

But from another standpoint, the fate of the Aztec Empire was sealed in the very first meetings of the emissaries of Moctezuma with Cortes, when they gave him gifts of gold and silver that Sernal Diaz valued at over 20,000 pesos de oro. Prescott, writing in 1947, valued each peso de oro at $11.67 U.S. Dollars. The Spanish appetite for gold was whetted, making the Conquest inevitable. But had Cortes failed, the next expedition, perhaps without an interpreter, would certainly have shed more Mexican blood.

Then too, had Cortes met with no success, the Smallpox epidemic that raged in the Aztec Capital might well have spread throughout the entire empire. By destroying the city, he perhaps saved the country. Bernal Diaz wrote: "When we entered the city every house was full of corpses. The dry land and stockades were piled high with the dead. We also found Mexicans lying in their own excrement, too sick to move."

After the Conquest, Cortes, with a wife in Spain, arranged to have Marina married to a Castilian knight, Don Juan Xamarillo.

Soon thereafter she disappeared from history.

But she had borne Cortes a son, Don Mahin Cortes. While many other Indian women were impregnated by Spaniards, we have no record of their fate. Hence, if modern-day Mexicans are a blend of Spanish and Indian blood, Doñña Marina's son was the first "Mexican" whose career we can follow. He rose to high government position and was a "Comendador" of the Order of St. Jago. In 1548, accused of conspiring against the Viceroy, he was tortured and executed.

In more recent times, the term "Malinchista" has been used by some to describe those who dislike Mexicans. But Doñña Marina deserves better. A fearless, loyal and determined woman, she was a heroine who helped save Mexico from its brutal, blood-thirsty rulers--and in doing so she played a major role in fashioning what is today one of the most dynamic societies in all of Latin America.